Boaz Weinstein’s Saba Capital recently executed a significant sale of Credit Suisse-related securities, crystallizing positions in one of the highest-profile banking collapses in recent memory. Financial Expert at Rineplex analyzes what this liquidation reveals about distressed debt markets and where sophisticated investors see risk-reward ratios shifting in the post-collapse environment.

The Credit Suisse Unwind Continues

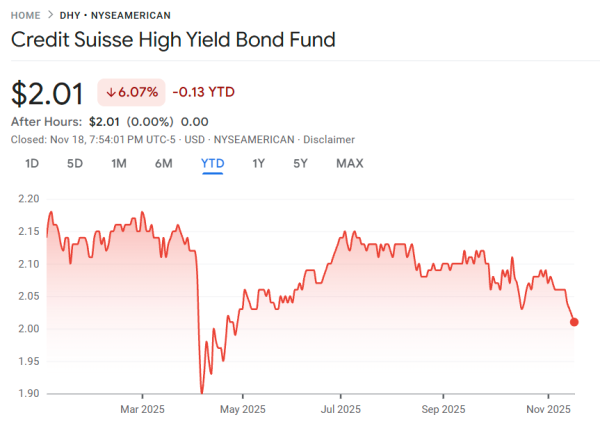

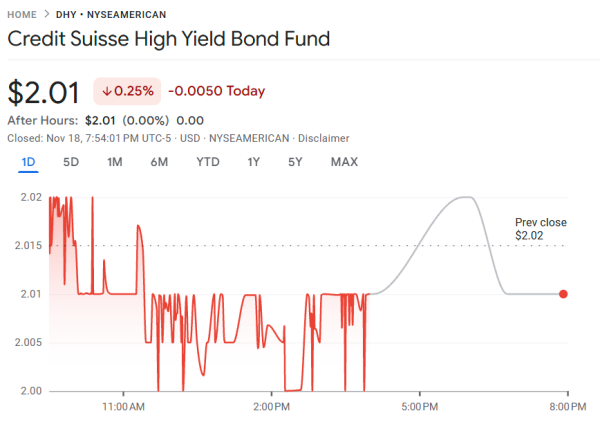

More than a year after Credit Suisse’s emergency merger with UBS, the reverberations continue spreading through global credit markets. Securities tied to the failed institution trade at prices that reflect everything from regulatory uncertainty to counterparty concerns. Saba’s decision to exit positions now suggests the hedge fund has extracted what value it could from the situation.

Distressed debt investing requires patience and strong stomachs. Positions often take years to mature as bankruptcy proceedings, restructurings, or mergers play out. The fact that Saba is selling now indicates either that recovery values have reached acceptable levels or that better opportunities have emerged elsewhere. Both interpretations carry implications for broader credit markets.

Analysts point out that the timing coincides with renewed volatility in European banking stocks. While the acute crisis phase has passed, lingering questions about banking sector health continue creating uncertainty. Sophisticated investors like Weinstein typically move ahead of broader market recognition, making their positioning decisions worth monitoring.

The magnitude of Saba’s Credit Suisse holdings isn’t publicly disclosed, but the fund’s reputation for taking concentrated positions in distressed situations suggests the sale represents meaningful capital redeployment. Weinstein’s track record in tail-risk investing and relative value trades has established him as among the more sophisticated operators in credit markets, making his positioning shifts noteworthy indicators of market conditions.

Distressed Debt Mechanics

Understanding what Saba likely held requires grasping the capital structure complexity of large financial institutions. Credit Suisse had issued numerous debt instruments with varying seniority, covenants, and redemption features. When the bank failed, each security’s position in the capital stack determined recovery values.

Additional Tier 1 bonds represented one particularly controversial element of the Credit Suisse collapse. These instruments, designed to absorb losses in crisis scenarios, were written down to 0 while equity holders received some value in the UBS merger. The unconventional treatment sparked lawsuits and created years of potential litigation overhang.

Senior debt holders fared better but still faced uncertainty about exact recovery amounts and timing. The merger structure meant Credit Suisse securities effectively converted into UBS obligations, creating basis trades between the old and new instruments. Arbitrageurs could exploit price differences, but the trades carried execution risk and required significant capital commitment.

The subordination waterfalls in bank capital structures create complex interactions where losses cascade from junior to senior instruments. Regulatory capital requirements add another layer, as different securities receive different treatment under Basel framework rules. Understanding these technical details separates successful distressed investors from those who get caught in value traps.

Contingent convertible bonds or CoCos represented another Credit Suisse instrument class that faced unprecedented treatment. These hybrid securities, designed to convert to equity or write down when capital ratios fall below triggers, behaved unexpectedly during the crisis. The lessons from how these instruments performed during Credit Suisse’s failure will influence future CoCo pricing across all European banks.

Broader Banking Implications

The Credit Suisse collapse exposed vulnerabilities in European banking that hadn’t been fully appreciated. Regulatory frameworks designed to prevent exactly this type of failure proved inadequate. The scrambled response and controversial bondholder treatment raised questions about whether similar situations might be handled differently in the future.

Contagion risk initially seemed contained, but aftershocks continue rippling through the system. Other European banks face heightened scrutiny and pressure to strengthen capital positions. The risk premiums investors demand for holding bank debt have adjusted permanently higher, reflecting reassessed tail risks.

The “too big to fail” doctrine faced real-world testing with Credit Suisse. The emergency merger solution avoided immediate systemic crisis but left numerous unresolved questions about resolution frameworks for major financial institutions. The ad hoc nature of the response suggests that formal resolution plans and living wills may prove less effective than regulators hoped during actual crises.

Confidence effects in banking prove difficult to quantify but enormously important. The Credit Suisse collapse demonstrated how quickly depositor confidence can evaporate even for centuries-old institutions. This fragility means that seemingly stable banks can face sudden crises that overwhelm capital buffers designed to absorb typical losses. The binary nature of banking confidence creates tail risks that traditional financial modeling struggles to capture.

Forward Guidance From Smart Money

When prominent hedge funds liquidate high-profile positions, markets pay attention. Saba’s Credit Suisse exit might foreshadow broader rotation away from European banking risk or simply represent idiosyncratic portfolio management. Distinguishing between these explanations requires monitoring whether other sophisticated investors follow similar patterns.

The sale completes another chapter in the Credit Suisse collapse story, but aftershocks will continue for years. Litigation over AT1 bonds will proceed slowly through courts. Regulatory frameworks will be revised. The full accounting of losses and recovery values will take time. For Saba, however, the time came to move on to the next opportunity.